Part 2: What Brought Me To DC

16 years in 16 paragraphs

The day I left the mainstream was that fateful day in 1964 when authorities announced that due to overcrowding my school district was being divided in half. A spanking new secondary school, Pascack Hills, would be erected to accommodate the overflow. Like it or not, that’s where I was headed. That meant I would not be attending Pascack Valley, the Sparta of the Northern New Jersey prep sports scene, the beloved facility whose prinicipal was Mr. Reaves, one of my best friend’s dad. There was not one iota of doubt in my mind that Pascack Valley was The Most Awesome High School In The Whole Motherfu**ing World. I’d dreamed of the day I could go there since second grade.

Every sports-obsessed kid in a district which included the northeast Jersey towns of River Vale, Montvale, and Hillsdale bled PV green — not that I had any prayer of personally contributing to its athletic legend or lore.

After barely making the age limit and basically skipping fourth grade for exhibiting signs of being a brain in a bottle, I was two years younger than anyone else in eighth grade and the second shortest kid in school — not exactly middle linebacker material.

Compounding matters, I was saddled with the gender-bender name “Lory” — a severe social handicap, to put it mildly, for the first fifteen years of my life.

Yet that was all OK. I would have done anything to honor PV tradition; I would have gladly served as waterboy for a juggernaut which had somehow fashioned concurrent winning streaks of 100 consecutive football games, wrestling matches, and track meets. Mr. Reaves wasn’t even a dick. The school was golden academically, too.

So I was effectively pre-programmed from the get-go to detest everything about Pascack Hills before I ever set foot there. Furthermore I considered it my duty [POW mentality] to escape from it whenever I could, like Steve McQueen in The Great Escape.

Most of the time, there was no escaping the 8:06 bell. Then I staggered down the antiseptic corridors, there for the duration including 4 mind-numbing hours of dead time: two study halls, lunch, and gym.

However, the mechanism for escape was conveniently in place.

Displaying a natural aptitude for stealth, I quickly mastered the art of cutting school and taking the Red and Tan Lines bus into midtown (Manhattan) to check out the art museums and take in matinées of various Broadway shows — often from the vantage point of a front row seat courtesy of Uncle Richard, a Tony Award winning lighting designer. My uncle would take me backstage and introduce me to the dancers — which meant I was in. No Pascack Hills cheerleader would look at me twice, but the lithesome Merce Cunningham dancers were cordial enough. Maybe after that I’d hop the IND line down to 4th Street in The (Greenwich) Village to gawk at the beatniks. Before long I was picking up a useful education.

One side effect of said excursions was that I soon settled into an academic standing at the bottom tenth of my class. I was so at home there that I never strayed.

On the bright side, after all these forays into The Big City, I now knew substantially more about the mythical Tuli Kufenberg and The Fugs than any other suburban kid. I could tell you where the Café Wha was. I knew where to buy bellbottoms on Bleeker Street, the better to shock my older classmates in the mean-spirited halls of Pascack Hills. I knew where all the music stores were on 48th Street, too; that information would come in handy when my rock ‘n roll career began in earnest.

That said, I was as far away from “the in crowd” as you could get.

The usual lineup of bullies, jocks, and cliques tormented anyone who wasn’t in with the in crowd.

That was enough to make the place “a drag,” but school administrators considered it their primary purpose in life to subject every male student, whether they were in with the in crowd or not, to week after week of mandatory marching drills in preparation to become cannon fodder for the Vietcong for the inevitable military service undoubtedly awaiting each and every prisoner one of us. The school board had a proclivity for hiring ex-drill sergeants for positions that were conspicuous male role models like Principal, Vice-Principal, and gym teachers.

Kommandant Principal Bart “Black Bart” DiPaolo was convinced he was doing us all a big favor by putting us through basic training. It’s not like I couldn’t see where his Paris Island schtick came from: it stemmed from the state of permanent war which had lasted from WWII through The Korean Conflict to Vietnam. Why wouldn’t he think we’d all be veterans one day, too?

The Hills’ heavy military vibe insured that my participation remained sporadic at best. But I was running my own War Room in my mind. After weeks of practice, I had finally mastered the art of forging my dad’s abstract expressionistic signature. I prepared the first volley:

“Lory is recovering from polio. His legs are incapable of bearing weight for more than five minutes without snapping” is one colorful and effective note that enabled me to forward march right out of gym class and halt by the nearest bus stop.

Setting off the fire alarm was another surefire tool at my disposal that I regularly employed to avoid marching drills or to get out of school altogether. Then my buddy John’s older sister Doris would come spring us, employing the Neulinger family’s plush push-button transmission Chrysler Imperial as the getaway vehicle.

Our status at the high school was so far off the radar that no one ever noticed we were gone.

Since I was incapable of differentiating between Pascack Hills and Stalag 17, by the time senior year rolled around in 1968, after four years of determined resistance, rebellion, and evasion, my college prospects were beyond bleak.

Mr. Kahn, my beleaguered guidance counselor, did his best to spell out my limited options. He’d identified four colleges, that weren’t community colleges, that, God willing, might possibly admit me provided Saturn and Jupiter were in trine.

The first three bastions of higher knowledge were:

- Defiance College somewhere in Ohio: right name, wrong state.

- Some military school in Virginia: although I could see where the Mr. Kahn was coming from with the need-for-discipline angle, that wasn’t gonna happen. A widely accepted myth at the time was “military service makes a man out of you.” I had already noted after watching the nightly news and popular TV shows like Combat and 12 O’clock High that military service was likely to make a quadriplegic man out of you. Pass.

- Ithaca College in upstate New York: my mom, the nicest human being who ever lived, who’d married into the Kryptonic moniker Connie Kohn (pronounced “con”) drove me up there one frigid February day. At 5 PM the temperature was minus 15 degrees and plunging a degree a minute. Underground tunnels connected the buildings. That brought to mind the tunnel Steve McQueen and company dug in The Great Escape — that flick was stuck in my mind. Ithaca was basically Siberia with textbooks.

Only one college hard up enough to even think about accepting me remained on the list.

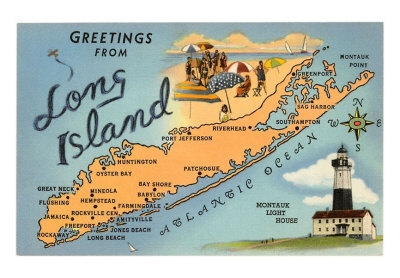

It was a new branch of Long Island University, Southampton College, located some place called the Hamptons.

I’d never heard of the Hamptons or the college. I perked up a bit when I saw a brochure picturing a nice-enough campus situated in the general proximity of a beach. When it came to beaches, the Jersey shore was pretty much all I knew.

“Lawn Guy Land,” as the locals pronounce it, isn’t really all that far away from northeast New Jersey as the crow flies. If you take the George Washington Bridge and follow the Cross Bronx Expressway over the Throgs Neck Bridge, you’re there. Nonetheless, I’d rarely been east of Huntington, home of the ritzy Huntington Town House, rival to Leonard’s of Great Neck as the place for bar mitzvahs, bas mitzvahs, and wedding receptions. If you were from the tri-state area, you were Jewish, and you weren’t an orphan, you’d been there a half dozen times times before the age of 14.

Cultural anthropology on the male side encompassed plenty of sharkskin suits, the scent of deservedly defunct aftershaves like Brut and Hai Karate, and combed-over hair; on the female side, a beguiling assortment of honeys sporting beehive hairdos wore space-age miniskirts, their orthodontically-corrected teeth framed by pink Yardley lipstick.

Any given Saturday there would be five or six receptions going on simultaneously. Each had its own band cranking out standards like “Moon River,” “Bewitched Bothered and Bewildered” and “Fly Me To The Moon.” Impressive trays of catered delicacies were there for the taking, laid out appealingly on buffet tables which were beat to hell but you wouldn’t know it cause starched linen tablecloths were draped over them. As soon as one tray of cold cuts was gobbled up, it was instantly replaced by the attentive, white-gloved staff.

If you were invited to one event, it was no big deal to crash them all without anyone being the wiser. Chopped liver turkeys and ice sculptures — swans, more often than not — were in abundant supply.

One bright spring day Connie Kohn and I drove out to Southampton in the family’s Rambler American station wagon (our other car was a beige Chevy Bel Air; Henry Kohn was too conservative to spring for a two-tone Impala).

One bright spring day Connie Kohn and I drove out to Southampton in the family’s Rambler American station wagon (our other car was a beige Chevy Bel Air; Henry Kohn was too conservative to spring for a two-tone Impala).

My first impressions upon setting sight on the campus were shock and disbelief — it was altogether possible that the next four years of my existence would take place no more than a hundred yards from a pristine beach where assorted nubiles in polka dot bikinis would be anointing themselves with Baby Oil (SPF 0) and asking for help slathering their backs. Waves were lapping upon the shore. Seagulls cawed, cleverly dropping snatched bivalves onto the parking lot asphalt before flying off with the edible matter, leaving behind the shattered remains. A marina and a neighborhood bar — where six months later five hundred of us would huddle shoulder-to-shoulder ecstatically watching Broadway Joe Namath’s Jets dissect the heavily-favored Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III on a 10″ black and white TV— were literally a stone’s throw away.

On a hillock in the center of the campus stood a picturesque windmill. I was unaware there were any windmills west of Holland. It was a curious sight. I mentally compared it to the underground tunnels of Ithaca and decided it was a feature I could live with.

Cute coeds in short shorts were scurrying off to class — Chemistry, Biology, whatever.

Cute coeds in short shorts were scurrying off to class — Chemistry, Biology, whatever.

Then Mom and I were driving into the village of Southampton, past mile after mile of immaculately trimmed hedges that guarded old-world mansions. Each was more spectacular than the next. Main Street Southampton, with its waspy shops like Lilly Pulitzer, cobblestoned sidewalks, and tulip beds ablaze, could only be described with a word that never occurred to me in the burbs: “charming.”

Grabbing a gourmet lunch at an apothecary/luncheonette I would have gladly eaten every meal at for the rest of my life, I learned that the easternmost tip of Long Island — from The Hamptons out to Montauk — was a fabulous summer playground for the rich and famous. In those optimistic times, when dreams were apt to come true, rich and famous were adjectives that I aspired to — my tendency toward slacking notwithstanding.

Was exile to this pristine and privileged parcel of God’s Green Earth going to be my punishment for finishing in the bottom tenth of my class?

Dear God, it was!

College daze begin

As my college phase began at the tender age of 16, mercifully I’d had a growth spurt and had hit the weights a bit, too. I’d also grown a very respectable mop of long hair; theoretically, the moptop sent a signal to “chicks” that I was “a groovy guy.” Despite the upgrades, I wasn’t exactly oozing confidence coming off a run of 4 years without a date in high school.

In other words I was ill-prepared for the warm welcome les demoiselles de Long Island had in store for me out on the dunes. Faster chicks from “The Island” looked me over and concluded, remarkably, that I was a) incredibly cute, b) really fun to be around, and, c) safe to have over for sleepovers thanks to my “unisex” name, which was still Lory. Over the course of a summer, a huge handicap had turned into a highly desirable asset. I quickly discovered that being “one of the girls” had its advantages.

Southampton College was the antithesis of Pascack Hills. At this school by the sea, I was instantly accepted as one of the guys, too. I was a longhair, I was against the war, and I liked to get high. In other words I had everything going for me.

No longer in hate with school, I reverted back to brain-in-a-bottle mode and began racking up straight A’s just to prove that I could.

I’d begun performing academically despite some major distractions. I’m talking about little life events like participating in sit-down protests of the Vietnam War, exploring how well weed went with Led Zeppelin I, and taking in numerous shows at the Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, a tantalizing two-hour Long Island Railroad ride away.

Since guitars are said to be a chick magnets, I began raising my voice in song. It was a good time in the history of mankind to be doing that — the folk era was in full swing. Working up my courage, I’d play at folk meccas in The Village like The Gaslight and The Bitter End.

Staying on the academic straight and narrow despite no end of distractions, I grew more emboldened. I even came up with a plan: get straight A’s at Southampton, transfer to an intermediate college, get straight A’s there, then apply to an Ivy League institution like Yale and kick major ass there.

The intermediate college I selected was American University in Washington DC.

Next: my “social skills” improve over the summer of ’69.

Table of Contents:

Part 1: IntroductionPart 2: How I Got to D.C.

Part 3: Film School in the Summer of '69

Part 4: Arrival in our Nation's Capital

Part 5: Metromedia

Part 6: Caught in a Vortex — The Vietnam Protests

Part 7: Aftermath

1 comment

Dr. Beth Fisher says:

Aug 8, 2013

Looking forward to reading the rest!